An Epigraphical Journey through Medieval Bengal : The name Vańga or Vangāla-deśa is quite old. We find it during the reign of Govinda Chandra (sometime between 1021–1023 CE) in the Tirumalai Sanskrit inscription of the Rajendra-Chola dynasty where it appeared as ‘Bhangala Desha’.[1] It also appears in more or less same fashion (in some cases ‘Bhangala Desham’) in a few Tamil inscriptions (namely as: வங்காளத்தேசம் in Tamil script) in Tamilnadu and some other places in southern India, in addition to a few other Sanskrit inscriptions of the Chandra dynasty discovered in Mainamati, Bangladesh.[2] The name Vanga also (connoting East Bengal [e.g., Vikrampura and the adjoining areas] in general) appears in a number of other Sanskrit inscriptions (e.g., Bhuvanesvar inscription of Bhatta-Vhavadeva, Edilpur Copper-plate of Keśava Sena, Madanapaḍa copper-plate of Viśvarupa Sena). [3] Likewise, it also appears in a few Arabic-Persian inscriptions (in the form of Bangāl in a number of Mughal inscriptions, e.g. Sherpur Masjid Inscription from the reign of Shāh Jahān dated 1042 AH/ 1632 CE). In an inscription dated 881/1476 found in Pichhli Gangarampur village (district Malda), from the reign of Sulṭān Yūsuf Shāh (879–886 AH/ 1474–1481 CE), we find a prayer for safety and protection of the inhabitants of Bang (البنغ) from any turmoil and that Bang may sustain till the day of judgment. It is only in the funerary inscription of Ḥājjī Shari‘at Allah dated 1255 AH/ 1245 Bengali Year (1839 CE) that Bangāl appears in a plural form as Bangālāt (البنگالات) most probably to imply also the adjoining areas of the greater Bengal (i.e., Assam etc.).

The origin of the name of Bhangala can be traced in ‘Ganga’ (Ganges in English, Padma in the later days’ usage in lower Bengal) which gradually turned into Bhanga, and then into Banga in the local dialects of Bengali for referring to lower Gangetic plain that was extended to the coastal line of the Bay of Bengal. The suffix ‘al’ (originally ‘ail’ [আইল] in Bengali) was a local native word meaning low mud embankment or earthen mound raised on all the four sides of a patch of land in order to hold salty sea water of the Bay of Bengal for extracting salt. This ‘al’ suffix was later added to Banga sounding very much like ‘Bangal’ altogether.

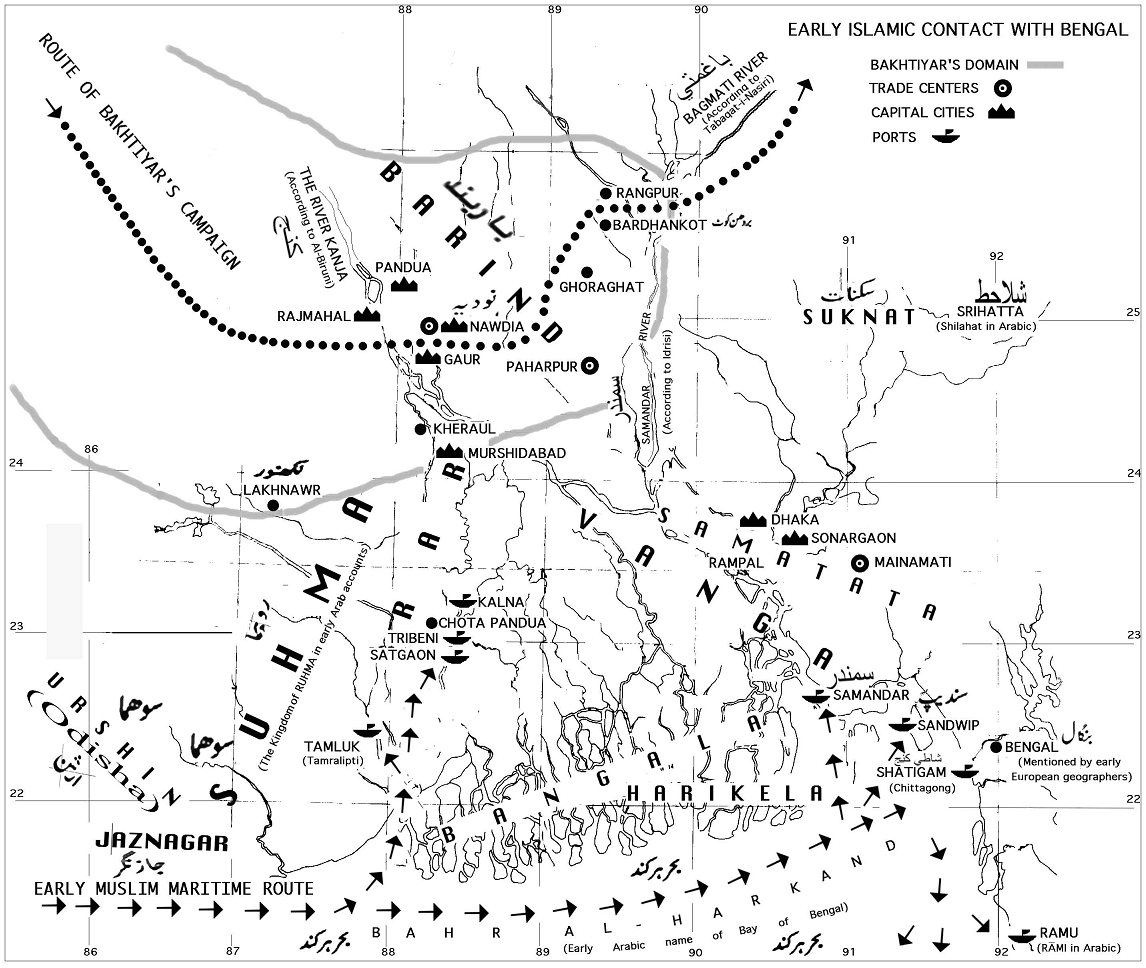

The word ‘Bangal’ has been best explained by Abul Fazal in Ain-e-Akbari very much in the same fashion. In addition to geographical reference, ‘Bangal’ also referred (and still refers in colloquial Bengali) to the inhabitant of lower Gangetic plain (what is known in English as lower Bengal). The historian Minhāj Sirāj al-Dīn was perhaps the first Muslim writer to refer to the name ‘Bilād-i-Bang’. Besides Banga, he also mentions a few other regions (or perhaps sub-regions) in this eastern part of South Asia, namely, Bihār, Bilād Lakhhanawati (لَكْهَنَوَتِىْ namely, Gauḍa Deśa), Diyār Suknāt (most likely the Samataṭa region comprising the present Sylhet district)[4] and Kāmrūd (Kamrup).[5] Shahr-i-Nawdia (نَوْدِيَهْ mistakenly transliterated as Nadia, but unlikely to be the same as the present district of Nadia in West Bengal), the capital of Lakṣmaṇasena (Rāy Lakhmaniyah according to Minhāj) was probably located on the bank of the old channel of the river Jahnabi (present day Bhagirathi) which changed its course westward later on. While it may possibly be identified with the present village of Nawdah[6] on the western bank of the currently dried river Pagla slightly westward of Mahdipur village in Malda district, West Bengal, it is more likely the village of Nawdapara, an archaeological site near Rohanpur railway station in Chapai Nawabgnaj district (not far from the city of Gaur), Bangladesh. This assumption is further supported by epigraphic evidence, as a number of inscriptions of the early Muslim rulers (e.g., a Persian inscription from Sultanganj, about eight miles north-west of Rajshahi city near Bijoynagar [the ancient Bijoypur, the capital of Bijoy Sen] from the reign of Sultan ‘Alā’ Dīn ‘Ali Mardān Khaljī in circa 1210–1213 and the masjid-madrasa inscription from Naohata [near Rajshahi, Bangladesh] from the reign of Balkā Khān Khaljī in circa 1229–1231) have been discovered in the areas not far from Nawdapara and Gaur.

The discovery of numerous thirteenth century inscriptions in North Bengal and many other historical evidences strongly suggest that Shahr-i-Nawdia the capital of Lakṣmaṇasena (Rāy Lakhmaniyah according to Minhāj) was the current village of Nawdapara, an archaeological site near Rohanpur railway station in Chapai Nawabgnaj district, not far from the city of Gaur. The grave of Bakhtiyār Khalji is also not very far from Nawdapara as he was buried atop a mound (that still contain unexplored ruins of an earliest Muslim headquarters there) in place known as Pīrpal near the village of Narayanpur, about eight kilometre southeast of Gangarampur Police Station (and not far from Devikot, the capital of Bakhtiyār Khalji) in Dakhshin Dinajpur district. It is important to note here that there is no any village, town, place or locality whatsoever in the whole district of Nadia (other than Navadipa) that carries the name of Nadia, Nawdia (نَوْدِيَهْ) or any place phonetically close to this name. None of the original sources (such as Tabaqāt-i-Nāsirī) gives any slightest indication of Bakhtiyār incursion to south or south-west Bengal where the present district of Nadia is located, rather all of them categorically mentions about his military activities which were limited to Lakhhanawati (لَكْهَنَوَتِىْ) and the areas situated northeast, north and northwest to it (such as Kamrup, Kamta, Bihar etc.).

Thus it was during the Sultanate period that both the term ‘Bangal’ both for this particular region (that was later on pronounced as Bangla in Bengali and Bengal in English and many other European languages) as well as for the people living in the region became popular in South Asia and elsewhere in the world. Ilyas Shah (circa 1342-1358 CE), for instance, was known as Shah-e-Bangaliyan (King of the Bengalis), Shah-e-Bangal (King of the Bengal), Sultan-e-Bangal (Emperor of the Bengal). The famous international university built by Sultan A‘zam Shah (circa 1390-1410 CE) in the city of Makkah in Arabia was named as the ‘Ghiyasiyyah Bengali Sultanate Institute’ (originally pronounced in Arabic as al-Madrasa al-Sultaniyyah al-Ghiyathiyyah al-Bangaliyyah). Using the name ‘Bengali’ for an international institute in West Asia, far away from Bengal, further popularized the term Bangal globally. Historically, this also inspired the growth of Bengali nationalism for the first time in every sense.

It was in West Asia that the science of ‘epigraphy’ emerged as an academic discipline as early as fifteenth century when mentors and academics at the International Bengali University (al-Madrasa al-Bangāliyyah) in Makkah, started looking at inscriptions with scholarly interest and historical intent. Fourteenth and fifteenth century Arab scholars in this Bengali seat of learning, such as Taqī al-Dīn Aḥmad ibn ‘Alī al-Maqrīzī (d. 845 AH/1441 CE) and Taqī al-Dīn al-Fāsī (775–832 Hijra/ 1374–1428 CE), studied inscriptions as an important source for regional history. Al-Fāsī’s work, for instance, was quite methodical in dealing with the epigraphs of Makkah as he surveyed the architectural remains of this ancient city and deciphered its inscriptions. He cross checked the dates appearing in the epigraphic texts with other historical sources to substantiate in a remarkably accurate way his findings about the history of Makkah.[7] Still, the credit for making the study of inscriptions as a distinct discipline goes to Jamāl al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn ‘Alī al-Shībī[8] (779–837 AH/ 1378–1433 CE). His meticulous study of Makkan tombstones and stelae established for the first time an extraordinarily and unprecedentedly high standard for scholarly epigraphic study. He can truly be considered the father of epigraphy.

Inscriptions can indeed be an important source for understanding civilization and culture of a region. Quite often, they serve as a missing link to the past offering many historical clues not available elsewhere. In spite of the many distinctive features, that each chronological period is distinguishable with, we notice a continuity in the epigraphic tradition of Bengal as a whole, be it ancient, medieval, or of the later days. An interdisciplinary approach in a true holistic spirit helps us greatly in getting a broader view and clearer understanding of a region. History, civilization and culture of Bengal can never be appreciated and evaluated properly without taking into account, for instance, inscriptions of various periods inscribed in diverse characters and in varied languages (such as, Sanskrit, Proto-Bengali, Arabic, Persian etc.). Bengal seems to be one of the earliest regions to use Persian for architectural inscription.

Most of the epigraphic records from ancient period (e.g., Sanskrit inscriptions) as well as from medieval period (e.g., Arabic and Persian inscriptions) begin by some kind of religious formula such as the praise of God etc. Some of the early Sanskrit inscriptions, such as Rampal copper plate of Srīchandra[9] (930–975 CE?), start with om (ॐ Hail, o supreme truth?). Likewise, many Arabic and Persian inscriptions begin by basmala (in the name of God) and/or divine blessing formulas (e.g., the bridge inscription of Sultanganj from the reign of Sultan ‘Alā’-Dīn) as well as Qur’ānic verse (e.g., Sian inscription dated 618 AH/ 1221 CE). Generally speaking, eulogy of rulers is an important theme found in Sanskrit inscriptions (e.g., Rampal copper plate of Srīchandra[10]) and also in Arabic and Persian inscriptions (e.g., Masjid-Madrasa inscription from Naohata from the reign of Balkā Khān Khaljī). Imprecatory verses are another feature occasionally found both in Arabic-Persian inscriptions (e.g., Waqf inscription for a Jāmi‘ Masjid from Dohar dated 1000 AH/ 1591 CE) as well as Sanskrit inscription (Madad-i-Ma‘āsh inscription for Ḥājjī Bhāgal Khān Masjid in Nayabari dated 1003 AH/ 1595 CE [Saka year 1517]).

Islam seems to enter in Bengal in its heydays as a torch-bearer of a new world order representing an advanced civilization of the time affecting the age old highly Sanskritized regional system led by the upper class of the population. After the advent of Islam in the region, architectural inscriptions became an important medium to convey visual, cultural, and spiritual messages to various people. Arabic and Persian inscriptions of Bengal are rich in textual contents, artistic manifestation and diversity of forms. They shed fresh light on the cultural dynamics of a crucial period of the history of the eastern part of South Asia. They also help us understand the complex religious transformation process in the region which, despite of having no direct geographical link with the central Islamic land, have a sizable Muslim population. In spite of the independent character of its historical experience, Bengal has also an important role in Islamic history in the global context ever since it was brought under Muslim rule in the early 13th century. During the period of powerful independent dynasties of the sultans as well as in the early period of the Mughals, its arts and sciences flourished, the cross-cultural ties of the region were broadened and Bengal enjoyed great prosperity. It was one of the richest regions in South Asia, nay in the whole world, which started attracting foreign traders as far as western Europe. Known as the grain basket of South Asia, its GDP reached nearly 12% of the whole world. It hardly ever witnessed any major famine until the advent of colonial rule in the mid-eighteenth century. Its extra-ordinary numbers of architectural inscriptions indicate to the massive building activities as well as public works during Sultanate and Mughal periods which are an indicator of a flourishing economy during those times. The title ḥājjī (e.g., in Nayabari inscription of Bhāghal Khān dated 1595 CE) appearing in a number of inscriptions suggest that many affluent Muslims travelled to Makkah by sea routes from various ports of Bengal and the region was well-integrated with the commercial system of the old world through its thriving maritime activities.

While one observes, perhaps with awe, a rich Islamic legacy in Bengal that grew and prospered over the past eight centuries, several intriguing questions regarding the consolidation of Islam in the region remain unanswered. One central question is why this particular region turned into a Muslim majority area while many other regions in the central, western and southern parts of the Indian Subcontinent did not go through the same transformation. Epigraphic evidences help us in finding fresh clues to many of these issues offering us a hitherto untapped treasure of diverse historical information. At times, they provide the most authentic source of documentation for the early history of Islam in the region. Many of these inscriptions contain some kind of religious message mostly in the form of verses from Qur’ān or sayings of the Prophet which can be helpful in understanding religious trends and transformations in the region. Inscriptions of medieval Bengal also indicate that Arabic and Persian languages became a cultural vehicle of the region regardless of ethnicity, religion, geographical or racial background, a trend continued until the beginning of nineteenth century when English gradually replaced them.

Inscriptions can sometimes provide quite valuable information about educational and academic activities and their patronage by ruling class. A thirteenth century Sanskrit inscription (Circa 1183-1262 Saka/ 1261-1340 CE) discovered in Malkapuram, Andhra Pradesh[11], for stance, throws some lights on the educational ethos of the time such as vidyā-manḍapa (as compared to madrasa in Islamic inscriptions such as Naohata inscription from the reign of Balkā Khān Khaljī). It also mentions āchārya and dīksā-guru (as compared to Qudwat al-Fuqahā’ wa ’l-Muḥaddithīn, in Bayt al-Siqāya inscription from Sa‘dīpūr dated 929 AH/ 1522-23 CE), detail of syllabus such as pada (words), vākya (sentence), pramānya (mode of proof/the method of validity) as compared to ḥisba (mathematical problem) and sharī‘a in Ẓafar Khān Madrasa inscriptions in Tribeni dated 698 AH/ 1298 CE. Indeed, a number of Arabic and Persian inscriptions offer names of many important personalities, ‘ulamā’ and religious teachers in addition to providing clues about religious institutions, seminaries (madrasa), their geographic locations, and exact dating of many historical events. Through analysing these epigraphic evidences, it is possible to develop classification of significant centres of learning and the possible linkages between them, transmission of ideas, evolution of important syllabi, student-teacher connections and intellectual genealogies. While these inscriptions suggest that madrasa institutions played an important role in disseminating education in the region, they also help us in constructing an intellectual history of medieval Bengal. It seems that many of the maktabs and madrasas were open to everyone regardless of religious background, creed, caste, colour or social status. The tradition continued even after the advent of colonial rule. In a survey done in 1835 in the districts of Murshidabad, Burdwan and Birbhum, Adam found that a total of 786 Muslim boys and 784 Hindu boys were enrolled in the Arabic and Persian schools (namely, maktabs and madrasas).[12] The trend still continues in these districts as well as some other parts of West Bengal where non-Muslim students are also enrolled side by side with Muslims in a number of high madrasas. Literacy, indeed, was not necessarily restricted (or limited) to a handful privileged ones as is generally perceived about medieval Bengal. If we include learning Arabic (and / or Persian) written characters also as an alternative mode of literacy, then this form of literacy was much more prevalent than it is commonly thought about. It seems to be a common practice of a sizable portion (percentage) of Muslim children of all classes living in rural as well as urban Bengal to be enrolled in the maktabs for their learning of Arabic and Persian written characters and the few extra-ordinary ones in madrasas for higher education too. Many of this basically literate class would also learn Sanskrit (and Bengali too in the later days) at their own initiatives as they grew up in order to play more effective and larger roles in the society. Still, it seems that all these educational activities hardly ever reached (touched) the lowest strata of the Bengali population who are identified at our modern time as Dalits (lowest in the Hindu caste system such as Nomo-Shudras), Adivasi (the original people who inhabited the land before the advent of the Aryans such as the Koch and Mech of North Bengal), tribal (such as Santals of the North-West Bengal) and nomadic peoples (such as the Bede of East Bengal) of the region. It is important to remember here that Bengali started emerging as an established written language slowly and gradually only with the establishment of Bengal Sultanate after it remained mere a spoken language in the region for a quite a long time. Persian, the official language of the time had an upper-hand during medieval period (perhaps more than Arabic, the academic language of higher education) whose long term effect can still be felt in day to day Bengali language, prevalent administrative and legal terminology in the region (such as zila‘ [district], mohkuma [sub-district], ‘adalat [court of justice], hakim [magistrate] and so one and so forth).

Interreligious relations are an important lens in understanding the history and culture of a region in a given period. One of the reasons that the Muslim dynasties lasted for a long time comparing to many other previous dynasties was that the Muslim rulers, in general, had a moderate approach to interreligious dealings. Indeed, they were much more tolerant than they are usually given credit for. None of the inscriptions record of any wilful destruction of any religious buildings or temples during Sultanate or Mughal period. The tradition of interfaith marriages, for instance, existed as indicated in Ghaibi Dighi inscription. It records that Lakshmi (a Hindu lady), mother of Khān Jahān Raḥmat Khān, built a mosque in Sylhet in the year 868 Hijra/ 1464 CE. These epigraphic evidences suggest religious harmony, cultural continuity and understanding among peoples of various identities in those days. We find, for instance, a devout Muslim Bhāghal Khān inscribing a waqf as well as a madad-i-ma‘āsh (endowment for maintenance of a religious edifice) text in Sanskrit language for a masjid (Nayabari inscription Saka year 1517) using local vocabulary what apparently seems to be borrowed from Hindu religious culture (e.g., mahsida mandira dini meaning, a religious temple [namely masjid]). It also appears that a prominent class of Bengali Hindus acquired a taste for Arabic and Persian language. Lāla Rājmal, for instance, inscribed (inscription dated 1102 AH/ 1690 CE) in Persian during the reign of Aurangzeb using elegant poetic expression to commemorate a bridge in Chapatali near Dhaka. On the other hand, Munshī Shayām Prasād, a clerk of an English colonial administrator (Colonel William Franklin) in early nineteenth century wrote the very first description of some inscriptions of Gaur and Pandua (Aḥwal-i-Gaur wa Pandua) in a superb and lucid Persian language. The message of sectarian harmony and tolerance can also be seen in the inscription of Garh Jaripa (inscription dated 893 AH/ 1487 CE), Bangladesh which contains a very typical Sunni phrase containing the names of four caliphs as well as a Shī‘ī religious formula of twelve sacred imāms. Accommodation of the two different sectarian beliefs in the same inscription suggests prevalence of overall social harmony, religious and sectarian tolerance, peaceful coexistence in medieval Bengal. The trend continued throughout the era of Mughal rule until the establishment of European colonial rule which adopted a policy of ‘divide and rule’ that sowed the seeds of a deeply rooted sectarian tension seriously harming the age-old social harmony. It is extremely rare to find out an inscription indicating social or religious tensions that unfortunately taint many parts of modern South Asia during these days. Some of inscriptions of Aurangzeb’s era record appointment of high-ranking officers in Bengal from the Hindu community as well as various minority sects indicating to the state policy of pluralism and religious tolerance in medieval Bengal. The common policy was, as it appears, to choose employees, based on talent, merit, efficiency and desirable qualities. Even black slaves (of Abyssinian origin) were successful in occupying high ranking positions that eventually led to their rule in Bengal as sultans at one point, though for a brief period (as affirmed by 13 inscriptions during 893-899 AH/ 1488-1494 CE). Unlike Gujarat, Sind or some other regions, the descendants of these African origins were gradually so well-blended into Bengali masses that it is impossible to distinguish them as a separate ethnic group anymore in the region.

Inscriptions also offered to the public in those days some practical information surrounding construction of prominent structures, identity of the patron, purpose of the monument in question, date of its construction, and so on. These valuable information help us reconstructing the socio-political context in which a given inscription was put into public view. Inscriptions some time form a significant element of Islamic architectural decoration due to their aesthetic appeal (e.g., Chand Darwaza inscription dated 871 AH/ 1466 CE). In addition to traditional types such as Kufi, thulth, naskh, riqa‘, rayḥanī, muḥaqqaq, many of them were rendered in various unconventional regional innovative styles such as tughrā and Bihari at times representing the natural landscape of riverine Bengal delta in a highly stylized form (see Babargram inscription dated 905 AH/ 1500 CE). Regional varieties of calligraphy, decorative motifs and ornamentation in these inscriptions are quite intriguing. The high standard displayed in the literary style of these epigraphic texts, their aesthetic exuberance and calligraphic taste remind us the cultural continuity in different regions what can be termed perhaps as “globalization of the medieval world”.

Another illuminating feature in the inscriptions of Bengal is the abundant appearance of titles reflecting cultural ethos of the period. Over-toned in religious fervour, these titles help us in understanding various religious and sectarian trends prevailing in the region. They also indicate the over-indulgence of the ruling class with flashy court culture, residue of which can still be found in the Arabic part of the Friday congregation sermon (khutba al-Jum‘a خطبة الجمعة). Ingeniously fashioned by the sultans of the bygone time to earn popular support, the pronouncement of the phrase ‘al-sulṭān ẓill Allah’ (السلطان ظل الله في الأرض فمن أهان السلطان فقد أهانه الله Sultan is the shadow of Allah on the earth, whoever dishonour the sultan, Allah dishonours him) is considered important enough to be forsaken even today. While one does find various texts in Qur’ān or sunnah [namely, ḥadīth or the traditions of the Prophet] implying that a just ruler (i.e., a genuine leader) is a divine blessing for mankind, this very text rarely appears in the same fashion in any of the earliest sources of Islamic traditions (namely, Qur’ān or ḥadīth), nor this phrase is ever used in the Friday sermon in the Arab world anymore. The use of such phrase in the name of religion at modern times indicates the blind adherence of many commoners (and more particularly the conservatives and dogmatists) to a set of fixed sacred texts without scrutinizing their relevance to time and space, the most detrimental factor to the future growth and development of any society or culture spiritually, religiously and intellectually.

Epigraphic evidences suggest that Islam gradually assimilated into Bengali life harmoniously and became part of the natural experience of the land, more as a new civilization refreshing the region with a novel cultural dynamism rather than mere a bunch of ritualistic tenets, unlike what the religion is perceived in many traditional societies. Islam thus emerged as a social system that well-suited the commoners in rural Bengal. Islam rapidly became a popular life style in the ever-growing picturesque Bengali villages as human settlement expanded along the delta side by side with the spread of rice cultivation and clearing forest areas of its otherwise low marsh land. Bengal’s wonderful ecological balance and natural harmony, symbolically represented in a number of inscriptions in abstract forms (e.g., Babargram inscription, dated 905 AH/ 1500 CE) left a strong imprint in its local Muslim societies through their popular expression in literature, art, architecture, culture and folklore. In its spiritual realm, Bengali Islam was accommodating enough to invite semi-Hinduised tribes, nomads and various other genres of local population into a fresh civilizational sphere to the extent that non-Muslims were free to visit mosques (as depicted in an earliest Arabic translation of a Sanskrit manuscript Ḥawḍ al-Ḥayāt), khānqāhs and madrasas. All these institutions played an important role in the religious, cultural and social growth in the region.

Bengali year (known in Bengali language also as Bangla Bochhor, Bangabda or Fosholi Shon), used commonly during later Mughal inscriptions to commemorate the dates of construction of mosques, is one of the most illuminating example of the cross-cultural and inter-religious influences over centuries among various religious communities in Bengal. It was introduced by emperor Akbar based on the calculation of solar Hijra year (not lunar Hijra year, commonly used by the Muslims for the purpose of religious observation) to develop a more scientific calculation as well as to improve tax collection process in harmony with solar agricultural cycles. This new Bengali year became the most popular and celebrated calendar among Bengali masses, both Hindus and Muslims alike. Besides celebration of ‘Notun Bochhor’ (New Bengali Year), this Bengali year (a modified and a more scientific version of solar Hijra year) is the only calendar used for all the Bengali Hindu religious observations including the sacred dates of pujas (e.g., Durga Puja, Kali Puja, Saraswati Puja etc.).

In an era when the communication revolution is gradually turning the earth into a global village, it is very important for us to understand the diverse and complex world of Islam which represents more than one-fifth (nearly 23%) of the human population. There is a tremendous transformation taking place almost everywhere in the lives, societies and political systems of these huge masses. These rapid changes are especially visible in the eastern parts of South Asia. The gradual rise of religious zeal in the region is causing a sort of ever-increasing tension between cultures. Unfortunately, one also observes regrettably among various peoples lack of proper understanding of the sensitivities as well as the dynamics of the original Islam that contributed once significantly to the formation of an attractive civilization in the medieval world. The resurgence of Islamic norms and values among the Muslims makes it even more important that we understand the history, religion and culture of the world of Islam in proper context and in a greater depth. Fortunately, inscriptions of Bengal have much to offer us towards understanding historical Islam. Thus, in spite of their many distinctive local cultural features, one soon discovers in these wonderful epigraphic treasures a vibrant message – unity within diversity – that is deeply rooted in the pluralistic Bengali culture in this eastern region of South Asia as much as in Islamic culture in historical as well as in global context.

Appendix

Madad-i-Ma‘āsh Inscription for Ḥājjī Bhāgal Khān Masjid in Nayabari Dated 1003 (1595)

ORIGINAL SITE: Two no-longer extant early Mughal mosques somewhere near the village of Nayabari at Aurangabad Bazar in Manikganj district, Bangladesh.

CURRENT LOCATION: Bangladesh National Museum (procured from Ali Ahmad Chowdhury of Dohar on October 27, 1978), Dhaka, inv. no. 78.1578.

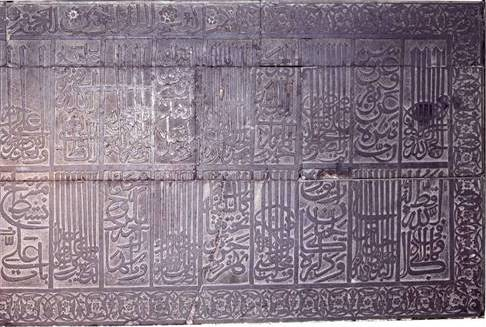

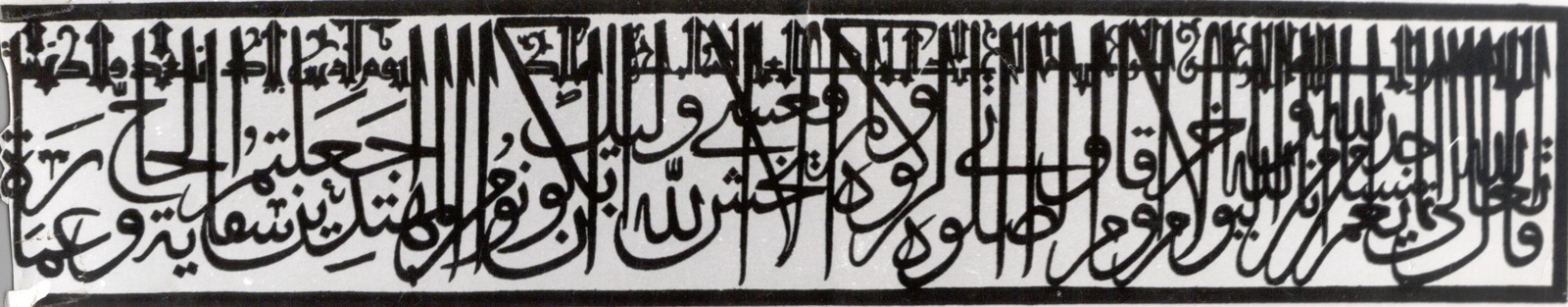

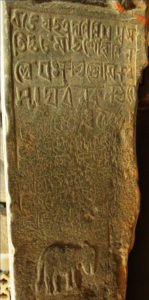

MATERIAL, SIZE: Grey basalt; the size of the Arabic-Persian inscription of the slab is 45 x 12½ inches (114.3 x 31.7 cm), while the size of the actual stone slab is 67 x 12½ inches (170.2 x 31.7 cm).

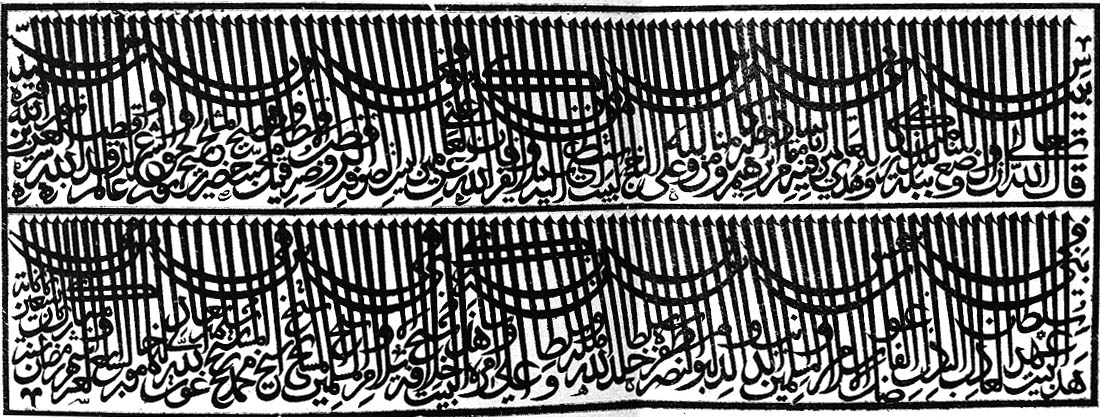

STYLE, NO. OF LINES: Crude naskh; fourteen lines.

REIGN: Circa 1003/1595, during the consolidation of Mughal rule in Bengal in Akbar’s reign (963-1014/1556-1605).

LANGUAGE: Arabic and Persian.

TYPE: waqf inscription.

PUBLICATIONS: Enamul Haque, “Samrat Akbarer tinti aprakashita shilalipi (Bengali text)”, Itihas, year 12, issue 1-3, (Dhaka, 1978); Mohammad Yusuf Siddiq, “An Epigraphical Journey to an Eastern Islamic Land,” Muqarnas, 7 (E. J. Brill, 1990): 83-108; Siddiq, “Epigraphy and Islamic Culture,” Muslim Education Quarterly, nos. 2-3, vol. 8-9 (1991-92): 52-73, 57-78; Siddiq, “Masjid, Madrasah, Khānqāh and Bridge,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, no 2, vol 42 (December 1997): 231-286; Siddiq, Riḥla ma‘a al-Nuqūsh fī ’l-Bangāl, 317-18 (See also its Persian translation by Layla Musazadeh, Katībah hā [کتيبه ها ], 400-402); Siddiq, Islamic Inscriptions of Bengal, 199-201; Siddiq, Bangāl ke ‘Arbī wa Fārsī Katbāt, 503-506; Swapan Kumar Bishwas, “Sanskrit Epigraph on the Two Sides of a Stone Slab Containing also an Islamic waqf Inscription in Persian during Akbar’s Era”, an unpublished work.

L-1 يا فتاح

ــــــــــــــــــــــ

L-2 قال اللّه تعالى

L-3 من جاء بالحسنة فله عشر أمثالها

L-4 [و]من جاء بالسيّئة فلا يجزى إلا بمثلها<مثلها>

L-5 قال النبيّ صلّى اللّه عليه وسلّم من كسّر عمارة الإسلام فقد

L-6 كفر محى اللّه عنه ألف ألف حسنات<حسنة> وكتب الله عنه

L-7 ألف ألف سيئات<سيئة> وفتح اللّه له باب النّار

من حفظ هذا البنيان وجد ثوابا في الدارين اين وصف

L-8 در قول نبي على دارين نواب محصن الدين فقير

سايه مختصر كرده الحب ازراه الله اين نگاشته شد محمد حماد

L-9 بنا شد [در] مدد إمام [و] معاش فقير كس كه خواهد شده

خدا يا رحم كن توهرد وجهان

بند ه ضعيف حاجى بها گلخان

ـــــــــــــــــــ

L-10 اين فقير در معاش دو مسجد هزار

L-11 بيگه براى للّه درراه خدائى تعالى

L-12 داد پانصد بيگه خمس أوقات

L-13پانصد بيگه جامع هردو

L-14 بارى بهم

Plate :

Translation:

O Opener! Allah the Most High said, “Whosoever accomplishes a good deed will be rewarded ten times over, and whosoever does an evil deed will be recompensed according to his evil [Qur’ān, 6:160].”

________________________________

The Prophet, peace and the blessings of Allah be upon him, said, “One who destroys any edifice of Islam becomes an infidel. Allah effaces thousands and thousands of his virtues and enters thousands and thousands of sins against him. Allah also opens for him the door to hellfire. He who protects this structure will receive [his] reward in both habitations.” This statement is from the saying of the Prophet about both dwellings. [During the time of] Nawāb Muḥsin al-Dīn, the faqīr, who cast but a faint shadow in this worldly life. It was for the love of Allah that Muḥammad Ḥammād inscribed it. It was built to provide madad-i-ma‘āsh (support for living) to the imām and faqīr, whoever happens to be so. O Allah, have mercy in both worlds on the humble servant Hājjī Bhāghal Khān.

________________________________

This faqīr has endowed for the sake of Allah as well as in the path of Allah the Most High one thousand bigha (1 bigha = 1,600 sq. yards) towards the maintenance of two mosques simultaneously, five hundred bigha for [a masjid for] the five daily prayers, and five hundred bigha for the congregational mosque. For each one of the two mosques, same allotment is being done.

Discussion:

This pillar-like stone slab seems originally to have belonged to a building of a much earlier date reused by Bhāghal Khān. The title ḥājjī suggests that Bhāgal Khān was an influential and accomplished man. In rural Bengal, ḥājjī often signified high social status since only the affluent could afford the pilgrimage to Makkah. The contemporary historical accounts tell us nothing about him. Though the other two inscriptions refer to the contemporary Mughal ruler Akbar, he is not mentioned here, suggesting that this is the earliest of the three.

The gradual switch to Persian from Arabic in this text reflects a significant cultural change in the country with the advent of the Mughals. Especially after Humāyūn returned from his exile in Persia, the region was increasingly influenced by the Persian language and culture that had begun to dominate every aspect of life in South Asia.

The crude writing, poor finishing, and grammatical mistakes in the text suggest that the job was done by a layman scribe hired locally, whose name is mentioned in the inscription as Muḥammad Hammād. While calligraphically insignificant, its importance lies in its statement of the endowment for two mosques built by Bhāghal Khān. Though paper was commonly used for legal documents, and more especially for the endowment of lands, using an inscription for such a purpose had the advantage that it was less likely to be stolen or to perish than a paper document, especially during a time of political turmoil. This is one of the very few Islamic inscriptions in Bengal where we find an endowment text.

This is the earliest epigraphic record of madad-i-ma‘āsh (lit., support for living), an important institution of the official grant system in Bengal, which also existed in other regions of South and Central Asia. Madad-i-ma‘āsh were personal, tax-free land grants typically awarded to people who had already founded mosques, madrasas, khanqahs or any other form of charitable religious institution. In many cases, madad-i-ma‘āsh were allotted simply to support imams, sufis, and those attached to the institution including visitors and the deserving poor taking shelter on the premises. The institution was in some ways similar to the Hindu tradition of devottar bhūmi (property endowed to the service of devi or god/goddesses). A number of Mughal farmans containing instructions for madad-i-ma‘āsh can still be found in the district collectorate rooms of the cities such as Sylhet and Chittagong. The income generated from these land grants was also dedicated to the maintenance of the mosque, madrasa, khanqah and even mazār (shrine) of popular sufis and pīrs (saints). In the lower delta region (known as Bhātī), sometimes madad-i-ma‘āsh were given to people who cleared the jungle and established mosques, madrasas, or any other religious edifice. Madad-i-ma‘āsh undoubtedly played an important role in settlements and the formation of agrarian societies in the unpopulated forest areas in eastern and southern Bengal. Though madad-i-ma‘āsh were sometimes offered to non-Muslims (particularly to the Hindus in the form of devottar bhūmi), they mainly benefited Muslims and helped indirectly in the consolidation process of Islam in the region.[13] The ḥadīth quoted in the text cannot be found in the al–Siḥāḥ al-Sitta (the six most authentic books of the Prophet’s sayings) or any other source, and its style does not match the idiomatic and literary expression of the sayings of the Prophet. It seems that the author of this epigraphic text was more anxious to ensure the protection of the mosque property than to ensure the authenticity of the ḥadīth. He may even have composed it himself apparently with a pious intention and then ascribed it to the Prophet to discourage people from damaging or vandalizing the mosque’s property.

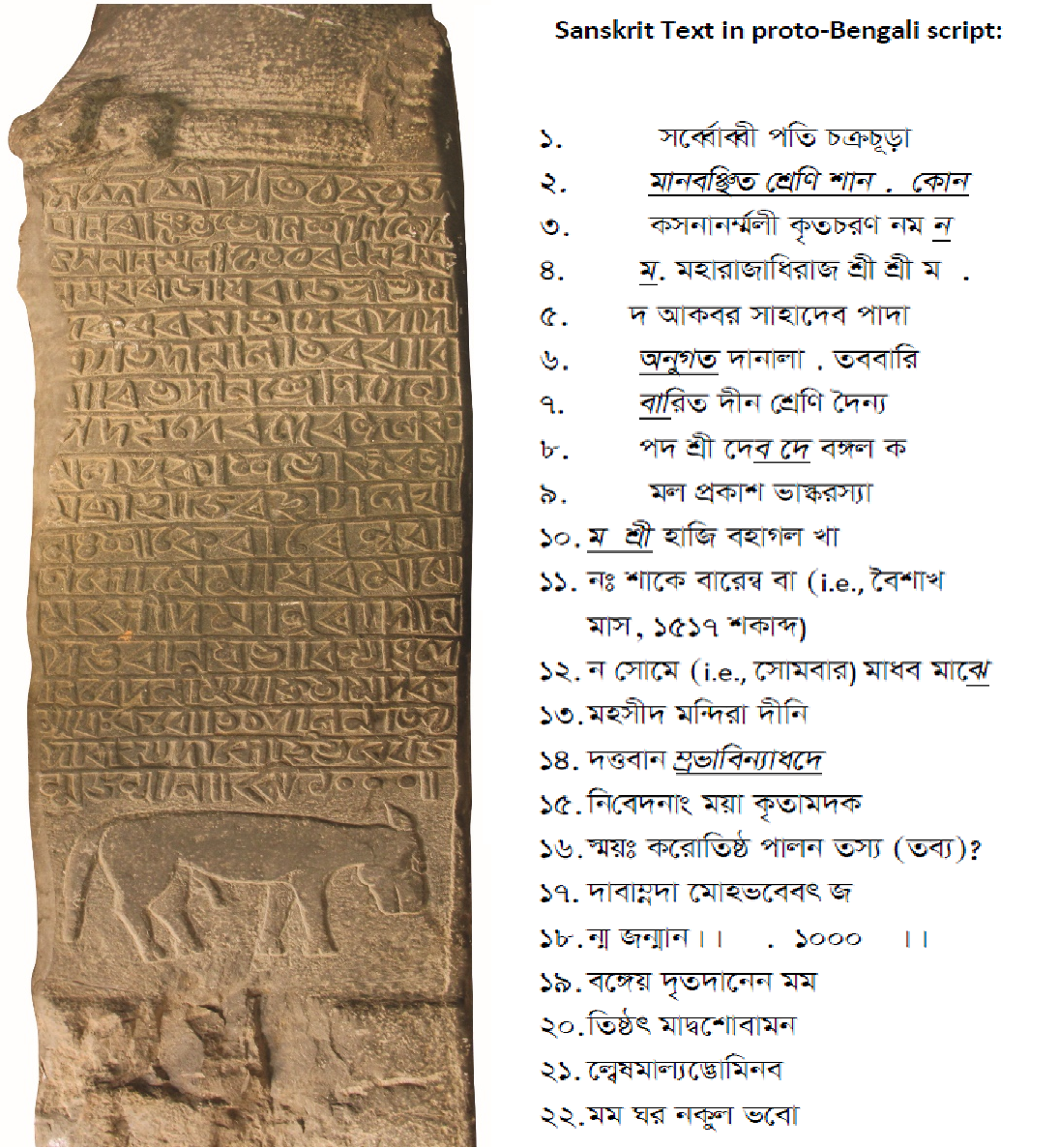

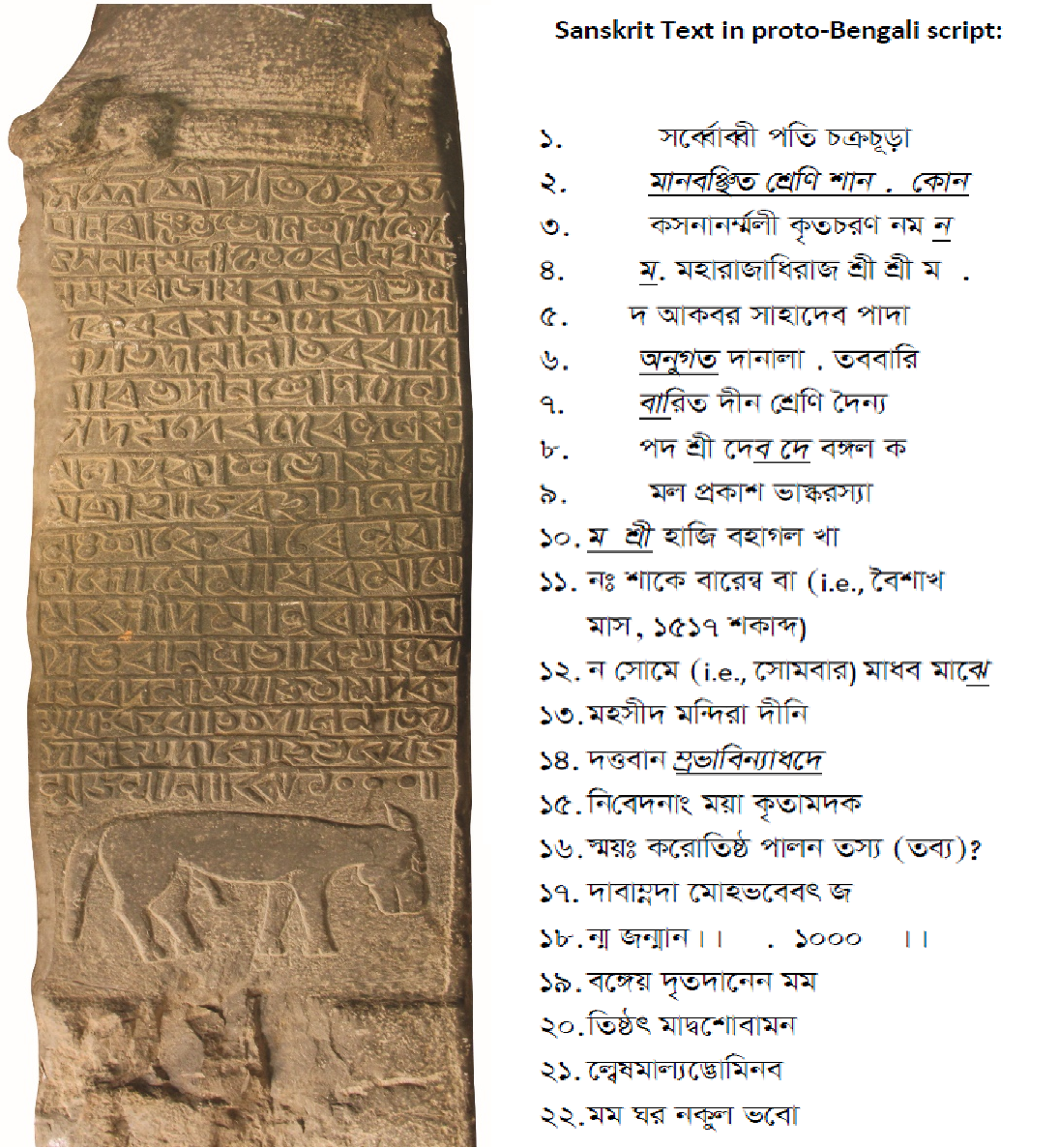

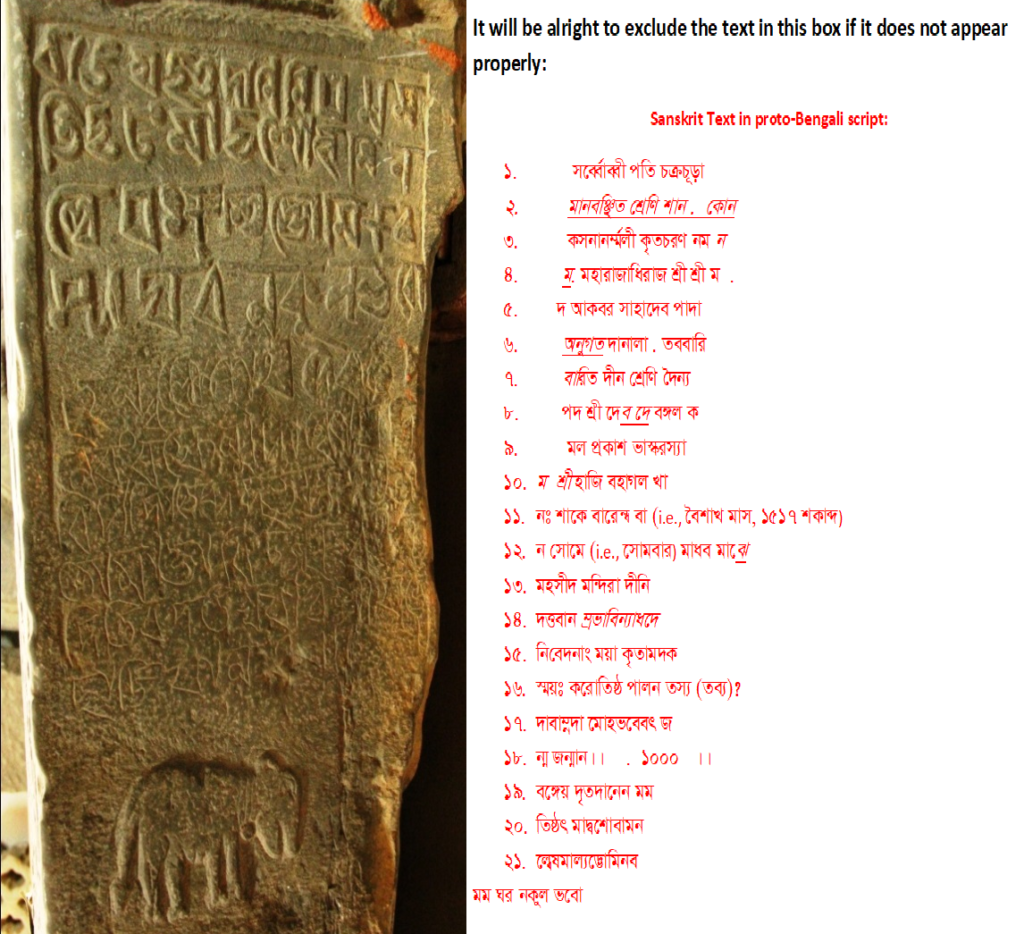

The undated Persian inscription of this stone slab is one of the three executed around 1003 AH/1595 CE during the period of political turmoil in Bengal just before Mughal rule was consolidated there. It is basically a waqf (endowment) inscription for two masjids. It contains a Qur’ānic verse, ḥadīth, and a Persian text that refers to a special form of endowment known as madad-i-ma‘āsh. Since it records the name of the same Hājjī Bhāghal Khān that appears in two other dated inscriptions from the same area, we can safely assume it comes from the same period. Our assumption is further supported by the fact that the slab has Sanskrit inscriptions in an archaic Bengali script on the other side which record the date in Shaka year as the month of Baishakh, 1517 (corresponding to Ramadan 1003 AH/April-May 1595).[14] It is important to note here that this part of Bengal was a predominantly Hindu region until very late in the Sultanate period, as the Sena Hindu dynasty continued to control a part of this area for a long time. They also left little in the way of architecture in the area. The Sanskrit text on the side of this slab records the establishment of a mahsid mandira dini (lit., the religious edifice of a mosque), by the same Bhāghal Khān, apparently a reference to the two mosques mentioned in the Arabic-Persian texts in this inscription.[15] Following is a conjectural reading of the Sanskrit text by Swapan Kumar Bishwas of Bangladesh National Museum (and then later on, the text was reviewed and translated by Kismatara Khatun [Suma]):

Translation of the Sanskrit Text (on the both sides of the slab facing the main Persian text):

- L 1 Dedicated to the all encompassing lord, the highest being on the earth

- L 2 the most adorable of all strata.

- L 3 A humble offer to the feet of the monarch,

- L 4 who is the king of all the kings, the most respected,

- L 5 Akbar, the God like monarch.

- L 6 Everyone expresses their allegiance,

- L 7 be he aristocrat, or humble one,

- L 8 [to this] sovereign of the earth, whose feet illuminate

- L 9 Bengal like a most distinct lotus .

- L 10 The highly respected Ḥājjī Bhāgal Khān

- L 11 in the Shaka year – of 1517 – – this pious act was initiated,

- L 12 in the day of – Monday – in the month of Baishakh,

- L 13 a masjid, an edifice for religious worship

- L 14 as a humble offering of mine (i.e. Ḥājjī Bhāgal Khān) with modesty

- L 15 and dedicated with utmost pleasure,

- L 16 for the sake of religious practice and devotion,

- L 17 for ages after ages with profound enthusiasm,

- L 18 In the year 1000 after hijra

- L 19 This endowment of mine will last forever in Bengal

- L 20 A Brahmin will never remain a Brahmin if he usurps.

- L 21 If someone fails to protect it

- L 22 he will reincarnate as a base creature in my household

* This study was made possible through generous grants from Fondation Max Van Berchem, Geneva, Switzerland, Iran Heritage Foundation, London, U.K. and Sharjah University, U.A.E. I am specially indebted to Mr. Tahmidal Zami, a noted researcher and historian, for helping me in various ways during this research work.

_______________________________________________________________

- Nani Gopal Majumdar, Inscriptions of Bengal, vol 3 (Rajshahi, Bangladesh: Varendra Redearch Museum, 1929), 3; D. C. Sarkar, Epigraphic Discoveries in East Pakistan (Kolkata: Sanskrit College, 1973), 37.

- For details, see Dinesh Chandra Sarkar, ‘Mainamatir Chandra Bangshiyo Tamra Shasantroy’, in Abdul Karim Sahitya Visharad Commemorative Volume, ed. Mohammad Enamul Hoque (Dacca: Asiatic Society of Pakistan, 1972).

- For details, see Nani Gopal Majumdar, Inscriptions of Bengal, vol. III, (Varendra Research Museum, Rajshahi: 1929), 6-9.

- A place by the name of Sakanat appears in a map in an early European work, His Pilgrims, by Samuel Purcha.

- Minhāj al-Dīn, Ṭabaqāt-e-Naṣirī, ed. W. N. Lees (Calcutta, 1863–1864): 148–153.

- It is a compound Persian name meaning new village (naw means new, and deh or diyah means village or villages [particularly in the low and marshy land]). The name itself bears a great sociological implication as it symbolizes the new settlements that started appearing in this hinterland right after Bakhtiyār’s campaign. The more accepted form of spelling in Bengal – Nawdiya (Navadipa in Sanskrit) – can also be interpreted as new lamp which is quite interesting since it symbolizes the advent of light (Islam) in the Bengal frontier with its conquest by Muslim forces. There were a number of villages that once bore the name of Nawdah in the districts of Malda, Chapai Nawabganj and Murshidabad, such as the present mauja (village) of Uttar ‘Umarpur, on the southeast of Gaur (or more precisely the present village of Mahdipur), about one kilometre west of Kotwali Darwaza. But it is the archaeological site of Nawdapara, near Rohanpur railway station in Chapai Nawabganj district which was most likely the capital of Lakhshman Sen conquered by Bakhtiyār. The site consists of a huge mound of old baked bricks of the type used in the ancient monuments in Gaur and the surrounding area. Local traditions still identify the ruins as Lakhkhan Sener Bari (Lakhshman Sen Palace) which had a back door (for emergency escape, known in Bengali as Khirki) opening to a jetty on Mahanada river. Another set of nearby ruins of a monument is locally known as Nawda Burj (sometimes also as Shāṛ Burj), apparently a victory tower built by Bakhtiyār after his sudden conquest of the Capital. The most brilliant discussion on this topic has been done by A. K. M. Zakaria (e.g., see Ṭabaqāt-e-Naṣirī trans. and ed. Into Bengali by A. K. M. Zakaria, 2nd edit. [Dhaka: Dibyaprakash, 2014], 32 – 60 [Introduction]).

- Taqī al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Ḥusaynī al-Fāsī al-Makkī, al-‘Aqd al-Thamīn fī Tārīkh al-Balad al-Amīn, ed. Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Qādir Aḥmad ‘Aṭā’, vol. 3 (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyyah, 1998): 419 (see also other editions, e.g. edited by Muḥammad Ḥamīd al-Faqī, Cairo: Muḥammad Sarūr al-Ṣabbān publisher, ah 1378, and Beirut edition by Mu’assasa al-Risala [n.d.]). al-Fāsī also surveyed a number of the oldest surviving mosques of his time in Taif and read their existing inscriptions; see, for instance, Shafā al-Garām bi Akhbār al-Balad al-Ḥarām, vol. 1 (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-’Ilmiyyah, 2002): 122 (see also other editions, e.g. edited by ‘Umar ‘Abd al-Salām Tadmurī [Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-’Arabī, 1405]).

- Muḥammad ibn ‘Alī ibn Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn al-Makkī al-Qarshī al-Shībī, al-Sharf al-A‘lā fī Dhikr Qubūr Maqbira Bāb al-Ma’lā, MS no. 354 s.f. 1179 in King Sa‘ūd University Library, MS no. 130/900 in Shaykh ‘Arif Ḥikmat Library in Madinah (copied in 1231 AH/ 1816 CE by Aḥmad al-Azharī), MS no 18325 in National Library in Tunisia (copied in 891 AH/1486 CE by Abū ’l-Qāsim ibn ‘Alī ibn Muḥammad al-Qaḥṭānī), MS no. 6124 in Berlin Library (copied in 1122 AH/1710 CE by Muḥammad Sa‘īd ibn Ismā‘īl al-Makkī). It is interesting to note that the prominent family of Shībī earned fame and respect in Makkah during the fifteenth century through their education and cultural activities. Quite a few of this clan hold various high positions in Makkah such as chief justice, muftī (deliverer of legal and religious verdict) and imām of the Grand Mosque. A number of scholars from this family taught at the famous international Bengali university in Makkah named as al-Madrasa al-Sulṭāniyyah al-Ghiyāthiyyah al-Bangāliyyah after its Bengali patron al-Sulṭān Ghiyāth al-Dīn A‘ẓam Shāh, the ruler of Bengal.

- Nani Gopal Majumdar, Inscriptions of Bengal, vol. III, (Varendra Research Museum, Rajshahi: 1929), 4.

- Nani Gopal Majumdar, Inscriptions of Bengal, vol. III, (Varendra Research Museum, Rajshahi: 1929), 6-9.

- This huge granite pillar (14.6 x 2.9 x 2.9 feet), containing 182 lines of writing, was found lying loosely at Madadam village in Thullur mandal. For other details, see Journal of Andhra Historical Research Society, vol. IV, p. 152; D. C. Sircar, Epigraphic Discoveries in East Pakistan, (Sanskrit College, Calcutta: 1973), 37.

- Report of the Bengal Provincial Committee of the Education Commission, Part II, (Calcutta: 1886), para 183; Selections from the Records of Government of India, no. CCV. 241; Bengal Educational Endowment Committee Report, Calcutta, 1888).

- Eaton, The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 259-66.

- Nalini Kanta Bhattashali, “Milan Mangal,” Desh [a Bengali weekly from Calcutta], 22 October 1983: 45-47.

- Ibid.

নবজাগরণ (ষাণ্মাসিক) – জীবনানন্দ ১২৫ তম জন্ম সংখ্যা – মননশীল সাহিত্য পত্রিকা

নবজাগরণ (ষাণ্মাসিক) – জীবনানন্দ ১২৫ তম জন্ম সংখ্যা – মননশীল সাহিত্য পত্রিকা